0 1

Houston, we have a problem

The arrival of Columbus in America in 1492 or the discovery of penicillin in 1928 are some examples of discoveries resulting from human error: inaccurate cartographic calculations in the first case and forgetfulness (cleaning a plate with a bacterial culture) in the second.

The sinking of the Titanic on April 14th, 1912, which claimed nearly 1,500 victims, has been considered the result of multiple human errors from the beginning of the project: design flaws, negligence, incompetence of the crew, poor safety decisions of all kinds, such as insufficient number of lifeboats or security guards without binoculars, etc.

On the other side of the scale, the Apollo XIII space odyssey in 1970 was described as "the most successful failure in history". Instead of landing on the moon, its three crew members managed to return to Earth after an oxygen tank exploded in mid-flight, which was reported to mission control with the famous phrase "Houston, we have a problem" (more accurately "we have had").

It is considered an example where human creativity and resilience overcame a catastrophic event in the most hostile environment possible, outer space.

Ineco has developed its Human First philosophy, a vision of safety analysis that integrates, in a new way, the technical and human aspects that have traditionally been studied separately

In all these cases, what is known in the field of risk analysis as "human and organisational factors", which is the science of understanding positive capabilities and skills (inventiveness, adaptability and learning, anticipating events, etc.), as well as investigating an intrinsically human characteristic: the ability to fail, i.e., to make mistakes, proved to be decisive.

0 2

We are fallible, but we are trying to improve

Throughout the 20th century, and particularly from the second half of the century with the scientific and technological impetus following two world wars, increasingly sophisticated industrial and transport systems were developed, with a greater weight of technological components. From 1945 onwards, in sectors such as nuclear power and commercial aviation, human failure was found to be behind 70-80% of accidents and catastrophes, as well as in the railway sector, among others.

Due to the intrinsic nature of their activity and their risk potential, the civil sectors where the first human reliability studies were considered, were aeronautics and aerospace, as well as maritime and land transport, the chemical and energy industry, particularly the nuclear industry, and medicine

Initially, the focus is on avoiding technical failures, which is the focus of the first safety studies. At the same time, philosophy, sociology and psychology took up and analysed the new concerns arising from technological development and scientific discoveries, especially related to the concept of uncertainty. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity and the development of quantum physics blew the mechanistic models of linear thinking based on direct cause-effect relationships. Trends of thought such as systems thinking and complex thinking propose overcoming the classical view of seeking knowledge of a whole by studying its parts in isolation.

Systems thinking (...) reminds us that the whole can be greater than the sum of the parts (...) instead of seeing an external factor as causing our problems, we see our actions as creating the problems we experience. Peter M. Senge, "The fifth discipline. The art and practice of the open learning organisation", 1992

By contrast, they believe that a socio-technical system, be it a car factory, a nuclear plant or an air traffic control service, is more than the sum of its parts, and that the interrelationships between the technical and human elements and the environment in which they operate are highly complex, dynamic and even contradictory. The objective is to manage the performance and behaviour of people within the system by focusing the evaluation on human interaction with the operation. Today, with Artificial Intelligence growing by leaps and bounds, with the debate on how to maintain human control over it on the table, understanding the variability of behaviour, in order to technologically 'fix' human errors, is becoming increasingly relevant.

03

Dissecting "human failure"

In the meantime, and assuming error as a connatural reality of human beings and discarding "zero risk" as unrealisable, the concept of "safety" was developed. ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organisation, created in 1944) defines it as "the state in which the risk of harm to persons or property damage is reduced to, and maintained at or below, an acceptable level through a continuing process of hazard identification and risk management”.

“Human error”,in this context , is not approached with moral connotations of any kind, but as "the behaviour of people that exceeds the tolerance limit defined for the safety of a system", according to the National Institute of Workplace Safety and Hygiene (Ministry of Labour, Spain). A system in which technical, human (people) and environmental elements are interrelated and interact with each other.

We cannot change the human condition, but we can change the conditions in which we work so that we have fewer mistakes and easier recovery. James Reason, psychologist, "The Human Contribution", 2008

Human reliability studies are a multidisciplinary area that brings together various branches of psychology and engineering, which have proposed different theories, analysis techniques and models on the multitude of factors, both internal and external, that affect human behaviour and decisions, concluding that people cannot be analysed as just another technical component.

A brief history of error

In recent decades, a variety of classifications (taxonomies) of human error have emerged according to different criteria, explanatory models, and study techniques and methodologies. Whether quantitative (based on probability calculations) or qualitative (expert assessment) approaches, or combinations of both, all have sought to unravel how, under what circumstances and why human failures occur, with the ultimate goal of preventing accidents or incidents.

Photo: Pablo Neustadt/Ineco

Conceptual models

In 1972 Elwyn Edwards proposed the SHELL model, which focuses on the interrelationships between the components of the system: Software , or non-physical elements such as rules, regulations, procedures, etc. ; Hardware, the physical structure of the work environment: equipment, tools and machinery. Environment , the internal and external conditions of the work environment; and Liveware, that is, people (individuals and teams).

On the other hand, the Swiss cheese model, formulated in 1990 by Manchester University psychology professor James Reason, synthesises human error as the consequence, not the cause, of latent or active system failures, represented by the multi-layered holes or slices (the "defences") of a Swiss cheese;: the incident or accident can only occur if several holes line up.

Human error assessment techniques

THERP (Technique for Human Error Rate Prediction), the best known, developed by Swain and Guttman in 1983. The tool is the human reliability "event tree". It is applied in the nuclear, medical, marine, chemical, aeronautical, transport and construction sectors.

SHERPA (Systematic Human Error Reduction and Prediction Approach) is a simple, qualitative and quantitative technique applied in the nuclear, mining, offshore and postal sectors.

HEART (Human Error Assessment and Reduction Technique) is a versatile and fast method of calculating human reliability, based on nine generic task descriptions. It has been applied in the nuclear, chemical, medical, aviation and railway fields.

Those specific to the nuclear field include SHARP (Systematic Human Action Reliability Procedure), SLIM (SuccessLikeli Hood Index Methodology), ATHEANA (A Technique for Human Error Analysis), TRC (Time Reliability Curve), CARA (Controller Action Reliability Assessment), INTENT, HCR (Human Cognitive Reliability Model) and NARA (Nuclear Action Reliability Assessment, a modified version of the THERP method).

In the aeronautical field, the successful Crew Resource Management (CRM) programmes were developed from 1979 onwards to prevent human error. Over the years, the scope of these programmes has been extended from the pilot (initially the acronym stood for Cockpit Resource Management ), to the entire crew, controllers, etc.

0 4

The pioneering contribution of Ineco: FARHRA, people first

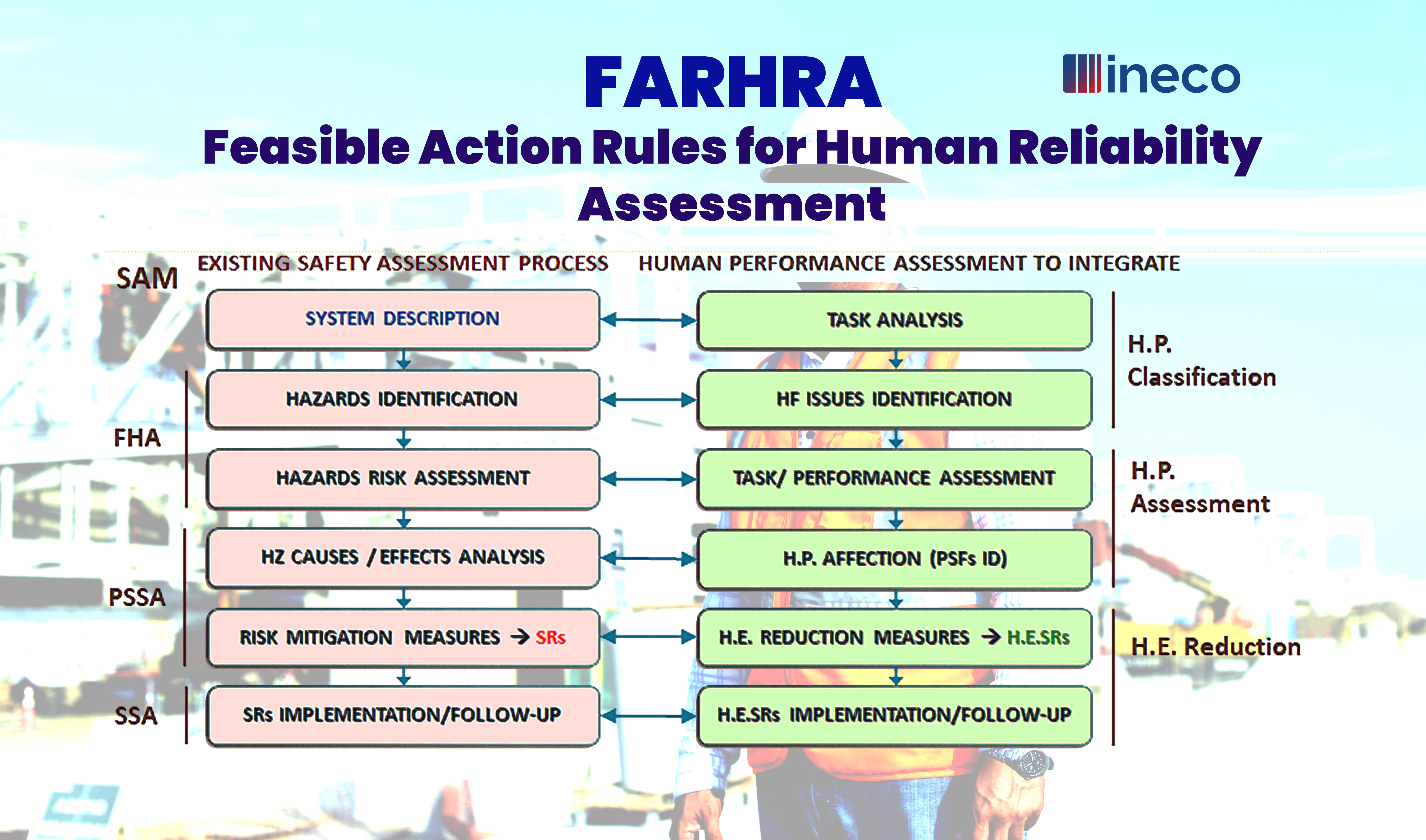

Within the framework of Human First, Ineco's own FARHRA (Feasible Action Rules for Human Reliability Assessment) methodology was developed, which integrates, for the first time on the market, human and organisational factors in risk analysis.

The starting point is that people's unsafe behaviours are not considered as causes, but as consequences of an environment and/or factors that can affect human performance (fatigue, stress, etc.), and can lead to incidents and/or accidents.

This methodology received the Global Safety Achievement award in 2019 from the Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO) for its pioneering approach. In 2022 and 2023, respectively, it has been adopted by Metro de Medellín (Colombia) and the European Space Agency (ESA) for its Galileo programme. In addition, in 2024 it is being used in projects with Adif, the Spanish state-owned railway infrastructure manager.

.

Ineco's outstanding contribution to ATM safety (...) is a true inspiration and a clear example of how CANSO members are introducing original innovations and valuable best practices worldwide. Simon Hocquard, CEO of CANSO, 2019

The task classification is based on five parameters, instead of the generic task types of the HEART method. In this way, an overall weight is obtained which, for each task, indicates its potential for error, i.e., how easy it is to make a mistake in its execution.

To connect to safety, cause and effect analysis explains the contribution of identified human errors to threats and their level of risk or criticality.

The factors contributing to the error are then determined. Instead of HEART's generic lists of Error Producing Conditions (EPC), from which the structure was taken as a reference, more usable lists of factors or PSFs (Performance Shaping Factors) affecting human performance were generated.

Finally, by combining the three aspects ( task error potential, error criticality and PSF performance factors) priority orders can be established for the final process: the reduction of human error. Initially, the NARA (Nuclear Action Reliability Assessment) approach was used, replaced and improved by the FARHRA method , which provides a larger set of measures and is more aligned with the usual approach in risk analysis in the transport sector.

Data science in the service of the human

Foto: kjpargeter/Freepik

Advances in data science and machine learning have also been applied to Ineco's Human Factors methodology, faced with the challenge of continuous improvement in safety in all modes of transport. For example, IneFIT, an algorithm and tool for measuring the fatigue index of shift workers, based on a BioMathematical Fatigue Model (BioMaF), has been developed.

At the same time, InFACT is a tool for analysing data from real accidents and incidents which, by means of machine learning algorithms, is able to extract trends about the underlying human factors.

Finally, to implement it in organisations, the company has developed HOPA (Human and Organisational Performance Assurance), a methodology for change management, which combines Eurocontrol's Human Factors Case methodology with Agile/Lean Management methodologies for risk detection, determination of mitigation measures and follow-up and monitoring of changes.

Ineco also continues to explore the applications of data science and machine learning in the field of human and organisational factors: methodologies are being developed to analyse the workload perceived by people when performing their tasks, and the algorithm for calculating fatigue indices is being improved.